Accidentally Archibald

A last-minute decision by Sydney-based artist Stephanie Monteith to enter the lauded Archibald Prize paid off.

True Blue Magazine - August/September 2018

Words by: Katrina Holden

The home of Stephanie Monteith is bursting at the seams with paintings and sculpture, oozing the warmth and eclectic charm you’d expect in a house occupied by creatives.

The family’s friendly sausage dog Patsy escorts me through the post-war home in Sydney’s southern suburb of Loftus, where Stephanie lives with her partner Dale Miles, a sculptor, and their six-year-old daughter Valerie.

At the kitchen table, surrounded by a vintage cupboard, an antique velvet settee and a large painting she produced, Stephanie discusses her life, work and the skeletons in her studio.

Neither eccentric nor flamboyant, Stephanie exudes a calm, measured presence. She imbues a serenity that resembles the poised women depicted in the works of centuries-old masters such as Rembrandt and Vermeer, whose paintings inspire her.

Stephanie has achieved what many Australian artists aspire to. This year, her work is hung among portraits by 56 other finalists in the coveted Archibald Prize at the Art Gallery of New South Wales. Even sweeter, a second landscape piece is one of 46 finalists in the Wynne Prize, Australia’s oldest art award, first presented in 1897.

Dressed in the same coat she wears in her Archibald self-portrait, Stephanie recalls her earliest brushes with art.

Born in Brisbane, her family moved to Sydney where, apart from a three-year stint in Papua New Guinea during her teens, she was raised in North Epping. After high school she went to Meadowbank TAFE, before enrolling at the University of New South Wales Art & Design school in Paddington.

“In those early years I think I was quite naive,” says Stephanie. “I wasn’t very strategic in my career planning. My mum would always say you need to have something you’re really interested in and that education was very important to give you independence in life. She said it’s important you find something of interest to pursue — for me, it happened to be art.”

After university Stephanie travelled and worked overseas in the UK, France, Spain and Central America.

“Visiting museums was part of my training. I like to look at art history and past art and really respond to that. I took sketchbooks the whole time I was away and I’d draw everywhere I went. I deliberately didn’t take a camera. I found drawing made me more focused on engaging with a place,” says Stephanie, who took inspiration from the likes of Turner, Bonnard, Velázquez and Goya, while she currently counts American John Curran as her favourite contemporary artist.

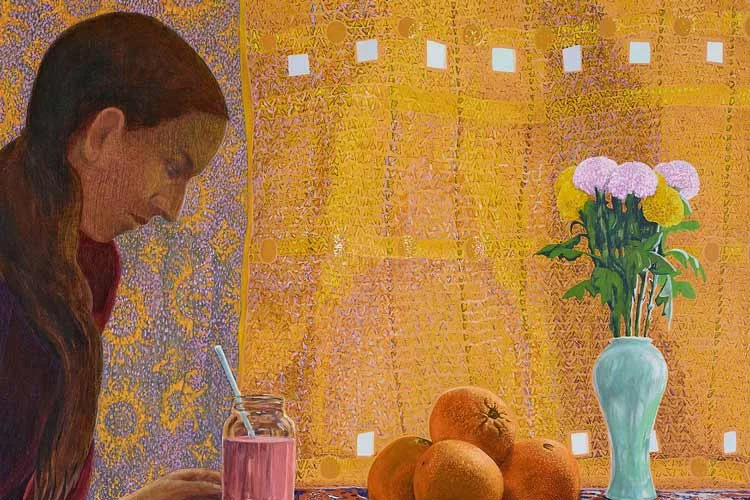

Stephanie’s training all those years ago certainly paid off. To date, her works have been featured in 11 solo and 83 group exhibitions. Her Archibald self-portrait, The letter — I really wanted to paint Germaine Greer, but she said ‘no’, took “ages” (more than a year) and she almost didn’t submit it.

“I decided to enter this painting just a week before the final due date, so it was quite a last-minute entry. I felt self-conscious about submitting a self-portrait, because the Archibald prefers that the sitter is someone ‘distinguished in art, letters, science or politics’,” explains Stephanie. “To claim the ‘distinguished’ title for oneself seems a bit egocentric, so my submission was based on the fact that I felt it was a strong painting that happened to be a self-portrait. Self-portraits have become quite acceptable as an Archibald entry.”

The title, as well, was not originally intended. But for Stephanie, the letter in her painting serves as a metaphor for the stereotypical Archibald experience.

“I asked Germaine Greer to sit and she said no. I never actually received a letter from Germaine, but I got a definite response,” she says. “Letters in paintings have happened a lot over time. Vermeer used them a lot — particularly women receiving a letter — and it’s like a communication of any kind. It could be many things; whatever the viewer wants to think. I like that sense that there’s a symbol of communication in there.”

The painting, Stephanie says, is quite “domestic” and, in a sense, she’s turned herself into one of her objects. “I don’t mind being in the limelight, but I’ve got this other side that’s fairly quiet. I think it encapsulates those ideas that you have a confidence but you’re happy to be in the background, too.”

It is almost accidental — or some might say fated — that Stephanie even appears in the painting. A late change of heart saw her step in for a skeleton she had intended to depict, as she’d done in earlier works, including her 2010 Living Room exhibition.

“I was painting some of the still life and I kept leaving the skeleton out. I thought, ‘I don’t want to do another skeleton painting right now,’ so I just put myself in the painting where the skeleton was,” she says.

It was a fortuitous decision. On her way to the train station one day, Stephanie received news — via email: the modern-day letter — she’d been accepted into the Archibald. “I was walking along with a silly grin on my face,” she remembers.

We head outdoors into the quintessentially Australian backyard, with a metal Hills hoist, a steel fence and a garden shed serving as her studio. A towering crimson bougainvillea bush spills over the fence from the neighbours, its colour matched by two crocheted woollen rugs Stephanie has positioned for added vibrancy and texture.

It was here, sitting on her white wrought-iron patio chair in front of her easel, that Stephanie completed two paintings that formed together to create her Wynne Prize entry, Backyard.

"Gardens aren't always built for paintings, but they are like the ultimate form of artwork," says Stephanie, who relishes the versatility of switching between studio and en plein air (outdoors) painting.

These recent accolades aren’t lost on Stephanie. With a newfound confidence, she plans to paint more landscapes beyond her own garden, with different types of flora and nature.

“I definitely want to pursue some portraits of others, too,” she says. “It’s just organising the time with them, because I do want them to be able to sit — I want to have time for that.”

Here’s tipping that, next time, her portrait subject will say “yes”.

The Archibald Prize will be on show at the Art Gallery of NSW until 9 September.

The touring exhibition then provides an opportunity to see all of the 2018 finalists in the following regions:

• Geelong Gallery, September 22–November 18, 2018

• Tamworth Regional Gallery, November 30–January 28, 2019

• Orange Regional Gallery, February 8–April 10, 2019

• Lismore Regional Gallery, April 18–June 17, 2019

MORE STORIES

Arresting Art

Artist Fintan Magee transforms vacant city corners into striking murals, sharing his ideas, sparking conversations and bringing beauty

to passers-by..

Stunning Shellharbour

Swim with sharks and traipse through untouched rainforest. Shellharbour, just 90 minutes from Sydney, is an adventure lover’s hidden gem.

Into the Green Cauldron

A getaway in the Tweed Valley offers just the right dose of relaxation, indulgence, nature and exploration.